This is Redfish Lake located at the base of the Sawtooth Mountains in central Idaho. I just spent several days there enjoying the slow pace of camp life. The days were long and the western, starlit nights, cool and crisp. I loved it, and having spent time there as a child, it was a nostalgic trip back.

This post won’t be recipe-oriented, although I’ll include one at the end. It will be more of a contemplative ramble on fish, nutrition and ecosystems. All have to do with health, both ours and that of the environment. We are inseparably linked.

When I camped at Redfish Lake as a little girl, there were “red fish” in the lake, lots of them. Idaho’s Stanley basin (and Redfish Lake) is the spawning destination of Snake River sockeye salmon. These wild salmon hatch from eggs and make the epic voyage from freshwater mountain lakes and streams to the distant reaches of the Pacific Rim. They do this in the spring as young fish, migrating downriver to the Pacific Ocean to spend 2 to 5 years in the ocean growing strong and large enough to endure the journey back home to the lake or river where their life began. The sockeye salmon from Redfish Lake must travel almost 1000 miles gaining over 6,000 feet in elevation to return to their spawning grounds where they provide life for the next generation and then die.

How amazing and beautiful is that? The power of nature. It brings tears to my eyes.

Okay, I don’t want to make this an environmental rant, but before the many dams were built in the Pacific northwest, millions of salmon returned each year to spawn. Redfish Lake was full of red fish, the brilliantly colored sockeye salmon. Now, how do they migrate past eight dams, reservoirs and industrial blockades? Most don’t, and it impacts so many different ecosystems that it’s impossible to measure the consequences.

Back when the salmon migration was uninterrupted by damming the rivers, millions of pounds of high-quality nutrients were “delivered” to the plants, animals and people of the Pacific Northwest. A recent study * documented 137 species that benefit from the ocean-origin nutrients these salmon provide to the environment. Eagles and other raptors, bears, wolves, coyotes, insects, aquatic species, and many plants all thrive on these nutrients. Minerals from the ocean have even been detected in the leaves at the tops of trees. For centuries, the indigenous people of the northwest were sustained by the salmon and their connection between land and sea. Rapid industrialization has changed all that.

Thankfully there are people working to restore the rivers and the wild salmon. Snake River salmon were listed as an endangered species in 1991 and although recovery efforts are underway, it’s been a slow process.

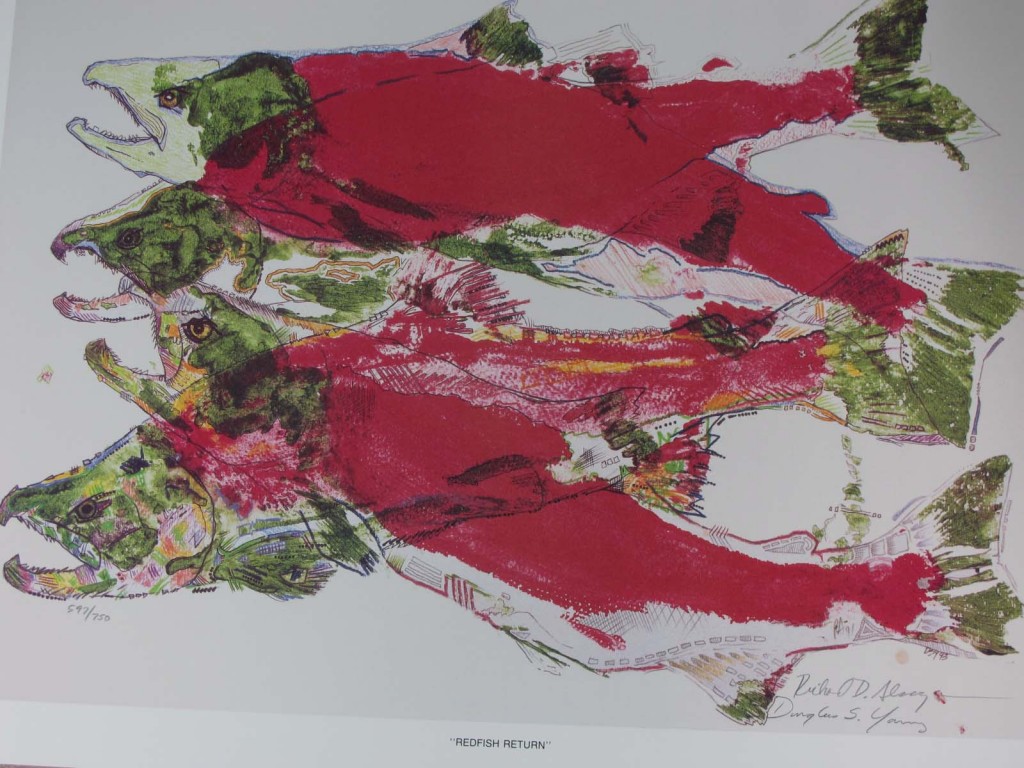

Below is a photo I took of a print by Douglas S. Young and Richard D. Alsager. It tells the story of the sockeye salmon and Redfish Lake. I bought the print for my fly-fishing-guide son who studied fish biology and river restoration at the University of Montana. He and his fiancée will be married next summer on the shores of Redfish Lake.

In 1991, four sockeye salmon returned to Redfish Lake in the Stanley Basin, their ancestral spawning grounds. This journey of over 900 miles is the longest anadromous fish run in the lower 48 states. Over the past few decades Idaho has seen sockeye numbers plummet from tens of thousands to just the three males and one female sockeye in 1991. These four fish were trapped and utilized as important genetic contributors for future sockeye to be spawned and released in Idaho. The four fish that returned in 1991 exemplify the power, strength, and resolve that is so prevalent and unique to Idaho’s anadromous fish.

This limited edition print was produced in order for Idaho’s sockeye to come to life artistically. The original piece of work was done by actually painting the fish and pressing them on paper. The areas vacant of paint were then filled in with various colored pencils and pens. We felt that if this fish was to leave this earth forever, that at least an artistic record of the actual fish would be left behind as a reminder to you of how beautiful they were.

— Artwork and narration by Douglas S. Young and Richard D. Alsager

I believe that a deeper understanding and appreciation of where our food comes from brings with it greater health, both physically and spiritually. You won’t be eating any Snake River sockeye salmon, but if you enjoy the rich nourishment and delicate taste of wild Alaskan salmon, express some gratitude for the fish and admiration for its strength before taking your first bite.

If you choose to eat fish, according to the Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch, wild-caught Alaskan sockeye salmon is a sustainable choice. Check here for a detailed guide to fish conservation and the best seafood choices.

* The above study information came directly from the Save Our Wild Salmon website (almost word for word).

how to roast wild Alaskan sockeye salmon

(full of nourishing fats and healthy protein)

what you do

I see no reason to mess with this, just cook it as it is and enjoy the rich, deep flavor of the fish.

Preheat oven to 425 degrees. Place tin foil on a cookie sheet and lightly grease with olive oil. Carefully rinse and pat dry the salmon filet (any size). Pour a little olive oil in your hands and rub it on the entire fish. Place fish skin side down on the baking sheet. Sprinkle with a little sea salt and freshly ground pepper. Place in oven and cook for 10 to 20 minutes depending on thickness. Remove when fish flakes easily with a fork. Serve with lemon slices. Keep it simple. Appreciate the fish and enjoy!

My guy Fairbanks (Alaskan Malamute), doing some fishing at Redfish Lake. No luck.

Peace, love and river conservation.

Melissa

P.S. After writing this post, I ran across this wonderful blog (Idaho River Reflections), with an eloquent story (and gorgeous photographs) about the plight of the salmon. Please check it out.

Posted in Adventure, Nutrition Therapy | 23 Comments »